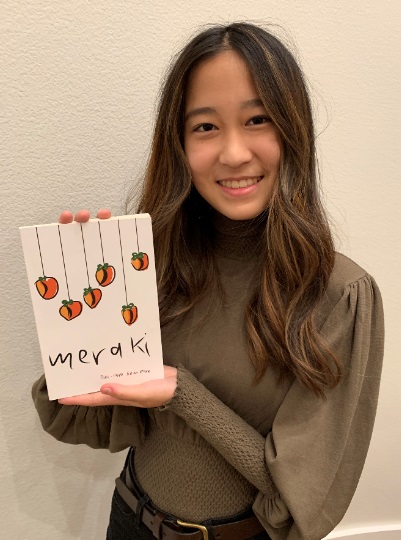

At just eighteen years old, Orange County School of the Arts senior, Tobi-Hope Jieun

Park, can boast an accomplishment few teenagers, and even adults, have achieved: she is a

published poet. Her poetry book, titled “Meraki,” which was published in 2020, has been

available for purchase via Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and other accessible stores. “Meraki” has

been in the works since she was a sophomore; however, it showcases the culmination of her

progress as a writer since she was just eight years old.

“Meraki” is a modern Greek word meaning “to take a piece of yourself and put it into

everything you do.” The 56 pages and 24 poems of “Meraki” reflect that definition, as it

illustrates Tobi’s life, her relationships with other people, her identity as a Korean American, and

how these experiences have shaped her as a person. As she puts it, “Meraki” is about “how

people have made me who I am and how they have made my writing into what it is.” In the

cover art of and the first poem of her book, titled “Persimmon Girl,” Tobi depicts an aspect of

her Korean identity and her childhood through the motif of persimmons. “Growing up, my

grandma used to feed me persimmons all the time and I remember being so fascinated by how

she cut the persimmons and how they never got sticky even though they were such a messy fruit.

It is an homage to my nana and it’s a really poignant image that is really personal to me.” Tobi’s

identity as a Korean and a Christian, and how those aspects of her life impact her perception of

the world, is the common theme behind her poems.

While certain parts of her poetry are geared towards her own intimate experiences, Tobi

also hopes to relate to other Asian Americans, and spread awareness about the Asian American

identity to others as well. “I think there’s a sense of mystique around the Asian American

identity and the culture and what it is not. I hope people realize that being Korean American is

very human and it is not very different from being anything else and how much we have in

common.” Tobi addresses the concept of solidarity among minority groups in various poems,

specifically in a poem called “we’re still not over ‘92,” which she co-wrote with a friend. “It’s

talking about Korean and black relations throughout the 1992 riots; we talk about how we have

so much more in common than we have differences.” The correlation between the timing of

“Meraki” being published at the same time of the pandemic, in the height of the Black Lives

Matter movement in response to police brutality and systemic injustice to African Americans,

and in the midst of the rise of Asian hate crimes, is not a coincidence. “Honestly I am really

grateful for the timing because I feel like what people need to say is being said and I’m really

glad that I could put out my work during a time where people are listening and people are

seeking to learn. I can talk about my identity and these conflicts because I have been passionate

about these issues for a long time. I think it’s really important that we are paying attention to

these issues and paying attention to artists of color.”

While Tobi’s view of poetry has always been positive and full of interest, few other

teenagers can relate. With the view of poetry being elitist and mundane, some view poetry as a

dying art form. However, Tobi counters that “I don’t necessarily think that poetry is dying out

but I do think it is evolving as an art form, and this isn’t a bad thing. I think it is important to

keep our options open and to analyze literature critically because there’s a lot to learn from

poetry as artists and readers. Nowadays a lot of us are leaning more toward shorter poetry and

spoken word poetry; we should lean into longer poetry and experimental poetry, as well as the

classics.” Tobi, a spoken word poet herself, is a huge proponent of this medium. “Spoken word

poetry goes by a lot of names: performance poetry, slam poetry. Basically it is writing a poem,

memorizing a poem, and performing it on stage, but it isn’t the same as reading because you’re

choreographing moves, you’re really emphasizing rhythm and word play.” In her generation,

Tobi believes this is how to remove the stigma of poetry being “snotty” with “strict rules.” “I

think it really has to do with education. When we are first introduced to poetry when we are in

school, it would be really great if we broadened the types of poetry we studied, because right

now as a high schooler, we really only studied the classics, which people find super old, difficult,

and long. My peers find it stuffy and not really relevant. But if we dabbled in some modern

poetry and spoken word poetry, that’s how you can break the stigma.” By not just reading poetry

written in Old English, teenagers can become more engaged in poems and expand their

intellectual boundaries. Some poets who Tobi recommend, who have also inspired her work

greatly, include Neil Gaiman, Franny Choi, and Phil Kaye. Tyehimba Jess especially has altered

Tobi’s perspective about poetry, through his work “Olio.” “It’s a really interesting book of poetry

about black Americans during and after Reconstruction and during slavery; it has had a really

big influence on me as a poet.” Currently, Tobi’s favorite book is Pachinko by Min Jin Lee. A

bestseller and winner of various awards, Pachinko follows the story of a multi-generational

Korean family and their immigration to Japan; Tobi finds the book beautiful and accessible for

all readers.

While publishing “Meraki” is a major accomplishment for Tobi, she hopes to continue to

expand her experience by writing more books and experimenting in different mediums, such as

prose or even music writing; she is open to any experience and opportunity. To writers and young

poets who want to follow in her footsteps, Tobi advises “I know this is such a cliche but just keep

writing, even if you feel like your writing sucks; the more practice you get, the more you read

other people’s work, the better it is going to get it is impossible to not get better. The main aspect

of writing is just writing and editing yourself and pushing through writer’s block or that fear that you’re not writing enough.” Tobi’s time at her high school, Orange County School of the Arts, or

OSHA, has also had a major impact on her writing. Her final advice is as follows: “Don’t be

afraid to put yourself in a community of writers. Going to OSHA and being surrounded by

people who were also passionate about writing really helped me improve and self reflect and

become the poet I am today.” Tobi’s advice as well as the sincere reflections of herself and her

view of the world in her poem book crosses generational and cultural lines. Reading “Meraki,”

supporting AAPI creators, such as Tobi, and listening to other stories of the POC experience, is

one crucial step to learning and acting during this time.